Fighting Threats Foreign, Domestic, and Glowing: Nightmares of the Cold War

by Lois Anne DeLong

Ahh the Fifties…cars with fins, drive-in movies, sock hops, poodle skirts…and radioactive monsters. The era that shaped the baby boomers is memorialized in classic television shows portraying a world that is orderly, peaceful and safe. In small town America, Mom stayed home cooking dinner dressed in heels and pearls, and Dad could solve all the family’s problems with an earnest talk with the kids once he came home from the office.

But, the 1950s were filled with other images as well, and were haunted by creatures that could, literally and figuratively, glow in the dark. The true monster of the era was the atomic bomb, which made its debut in the decade before and would truly cast its malevolent shadow as the Cold War grew through the 1950s. These walking nightmares would show themselves in ways both silly and serious, equally present in the local drive-in and on the evening news.

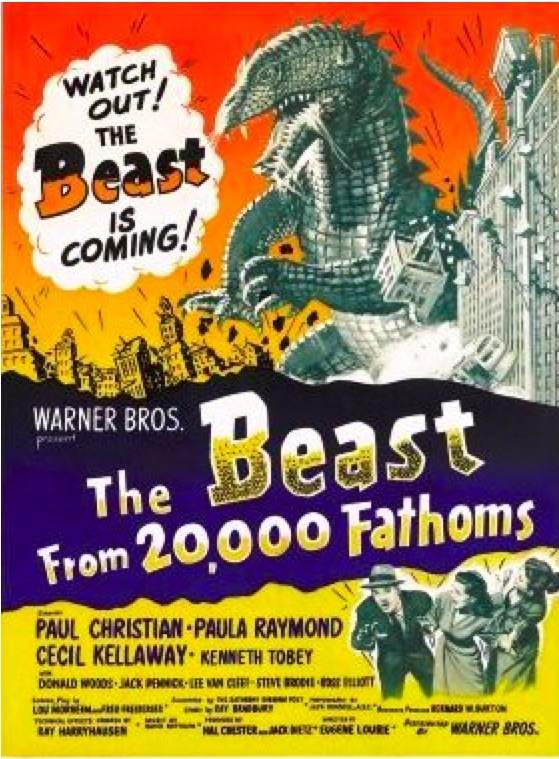

Original poster for The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953).

On June 13,1953, that fear began to take on a distinct popular form. That was the day The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms debuted in U.S. theatres. Directed by Eugène Lourié, a Ukraine-born film jack of all trades (set designer, production designer, and screenwriter, as well as director) who lived and worked in Paris till the mid 1950s, the film is considered the first of the “creature features,” that would scare and delight a primarily teenage audience throughout the decade (1). The film’s protagonist is a “Rhedosaurus,” a huge dinosaur awakened from suspended animation under the polar ice by nuclear testing. As the monster cut a hellish swath down the northeast coast and into New York City, it helped set the pattern for such cartoonishly nightmarish leading figures as the Blob, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, and the big daddy of them all, Godzilla. Indeed, some suggest the earlier film may have directly inspired some aspects of the acknowledged “king of the creatures” that would come to us via Japan in the following year.

American horror movies have always provided a mirror on the nightmares of our times. The first wave of movie monsters in the 1930s had several things in common: they were both literary (think Dracula and Frankenstein) and foreign in origin, and they played out their dramas in places like an obscure Transylvanian castle or a nightmarish English countryside. Even if a monster visited our shores, like the mighty King Kong, it was clearly a tourist from another world. Given the turbulence in Europe at the time, it's perhaps not surprising that our horror films had strong European accents. By the time we reached the Fifties, the threat had changed. Now the monsters were appearing in our cities, destroying our landmarks, and, whether we were ready to admit it or not, the evil was of our own making. Consciously or unconsciously, there is a glimmer of guilt in these films, as well as visible traces of the anxiety of living in a world where two superpowers could end everything with one phone call and the push of the button.

So exactly what do these movies say about our fear and guilt? Andrew J. Huebner of the University of Alabama suggests they present a mixed message. “Hollywood filmmakers of the 1950s did far more than simply broadcast Cold War fear—they wondered aloud about the consequences of science and technology for human life—and their wondering prompted audiences to wonder,” Huebner writes, adding that these films “did not speak with one voice, and often sent clashing messages within the same film” (2, pg.8). Huebner suggests that the overall confusion and anxiety of the American mind at that time led to responses to the films ranging from fear to nervous chuckles. He quotes the lead character from The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, a scientist named Tom Nesbitt (played by Paul Christian), asking the question "What's going on in our turbulent world today?" to which another character responds "Oh, death and politics. The comic page is the only thing that makes sense anymore" (2, pg. 8).

Eugène Lourié , director of The Beast. Picture courtesy of the Art Directors Guild Hall of Fame web site

Unlike many of the movies that followed in its wake, The Beast has a rather extraordinary pedigree. As an art director Lourié worked alongside such legendary French directors as Jean Renoir, Max Ophüls, and René Clair (3). The film’s plot was based on a short story by science fiction master Ray Bradbury, which had been published in the Saturday Evening Post as “The Foghorn.” Ray Harryhausen, one of the leading special effects artists of the time and an acknowledged master of stop-motion animation, created the Rhedosaurus. And its profitability ensured the monsters would continue being due on Maple Street (to paraphrase the title of a classic Twilight Zone episode). Made for $210,000, the film earned $2.25 million at the North American box office, and would go on to gross $5 million worldwide for its distributor, Warner Brothers (4).

Watching the film today, there are a few interesting elements to focus on. The black and white film starts with an off-camera narration about the nuclear test, giving it the appearance of a documentary. It also maintains a certain amount of ambiguity about the consequences of the nuclear test that sets the title character free. The lead character, Tom Nesbitt, is a nuclear physicist who is aware that much is still not known about the long-range effects of the bomb. Early on he admits to another character that “the cumulative effects” of the explosions are unknown and later in the same scene, when someone remarks that the tests would be “opening a new chapter” in science, Nesbitt follows up by saying that he hopes “we’re not writing the last chapter” for the world. In a final twist the same radioactive energy that creates the monster ends up destroying it when an army marksman fells the beast by shooting it with a radioactive isotope. The cure and the disease, in effect, are seen as one and the same.

Prof. Tom Nesbitt (Paul Hubschmid), Lee Hunter (Paula Raymond), and Prof. Thurgood Elson (Cecil Kellaway).

The film features a cast that would be largely unknown today, even to hardcore cinephiles. Nesbitt was played by a Swiss actor named Paul Hubschmid, though his screen credit here is Paul Christian. Hubschmid had a fairly long career in film and television, but not on this side of the Atlantic. Perhaps the two best known names in the film are Cecil Kellaway, a South African-born, Australian-trained character actor with numerous credits in American film and television, and Lee Van Cleef who in the next decade would join Clint Eastwood and Eli Wallach in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. The effects are naturally a bit simplistic by contemporary standards, though the monster looks less fake than the very flat simplistic backgrounds, particularly when the film location is supposed to be New York City. However, the end scene where the Monster is thrashing through Coney Island and is felled by the marksman from the top of the Cyclone is pretty spectacular.

Monster movies were to be a staple of the next ten or so years after The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms debuted and the radioactive catalyst that creates or frees the creatures remained a running trope of these films. As time went on, though, the films became sillier and any Cold War messages they started out conveying got lost along the way. The rare exceptions, such as Don Siegel’s brilliant original version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers—a commentary on 1950s conformity and the creativity-quenching activities of Senator Joseph McCarthy and his band of witch hunters—were all the more powerful because of the mediocrity of the genre as a whole. By the early to mid 1960s, monsters had joined female prisoners and bikers in the odd stew that became American B movies. The next time the monsters arose with any kind of serious intent was in the late 1970s, with the rise of the slasher films. By that point, there was no sense of the “other” in our monsters. Despite their ability to die and then return, Jason and Freddie Krueger were human. Monsters were no longer an alien presence. In the words of Pogo, “we have met the enemy and he is us.”

SOURCES

1. Brennan, Sandra. "Eugène Lourié”. Allmovie. 8 November 2010. Web. 9 April 2015.

2. Huebner, Andrew J. “Lost in Space: Technology and Turbulence in Futuristic Cinema of the 1950s,” Film and History, 40(2), Fall 2010, 6-26.

3. Weaver, Tom. Double Feature Creature Attack: A Monster Merger of Two More Volumes of Classic Interviews. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003, 202.

4. Van Hise, James. Hot Blooded Dinosaur Movies. Las Vegas: Pioneer Books, 1993.